Deunking Syria’s Brutal Civil War.’ Caused Bye Global Warming, Tracing Syrian Conflict Back To Iraq’s Civil War? Syria Remained At The Center Of The New Christian Religion Until The Seventh Century, When The Area Succumbed to Muslim Arab Rule?

The relationship between Iraq and Syria has a troubled history with many

contradictions. It has been strained during most of the countries'

recent history. Nevertheless, the two sides are so similar and close

that there have been projects to turn them into one entity ever since

the founding of postcolonial states in the Arab Middle East.

The first king in Iraq after its separation from the Ottoman Empire was also previously the king of Syria. However, as Iraq and Syria were under the control of two different powers (Britain in the case of Iraq, and France in the case of Syria), they were not governed by King Faisal I during the same period.

The Baath party failed to unify Syria and Iraq, despite the fact that the party’s ideology was based on the idea of Arab unity and its branches ruled the two countries simultaneously. This failure was a result of the unique relationship between the two, one which is characterized by strong similarities and discord at the same time.

Iraqi politician Ahmad Chalabi’s recent — albeit unrealistic — call to establish a confederation bringing together the two countries signals a continued lack of faith in the feasibility of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which set the borders of the two countries.

While that call lacks seriousness, the biggest paradox is that the al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS, also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) has become the first political-military organization to deal practically with the two countries as a single political unit.

An important aspect of the religious and sectarian divide in the region is based on the historic conflict in the seventh century between the army of Ali bin Abi Talib, the fourth Islamic caliph based in Kufa, Iraq, and the army of Muawiyah Ben Abi Sufyan, the Umayyad dynasty founder who settled in Damascus.

A great deal of the sectarian tension currently plaguing the two countries results from historical conflicts, and from telling the story of these conflicts in a way that serves the different parties in their current confrontations.

However, the issue goes beyond ideology, reaching actions on the ground. At a time when many people are talking about the need to stop the Syrian civil war from extending to Iraq, it is worth mentioning that the relationship between the two countries and their respective turmoil existed even before the outbreak of the protests in Syria.

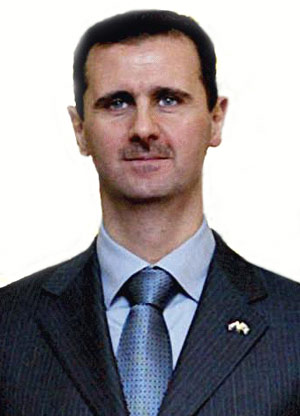

The political and social transformation in Iraq that followed 2003 had a significant effect on Syria. President Bashar al-Assad's regime tried to be in harmony with the will of the majority of Syrians in opposition to the war and its consequences, but probably for different reasons. Syria allowed the flow of foreign fighters to fight the US forces in Iraq. The insurgency, however, led to results that would affect Syria at a later stage.

Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees, including opponents of the regime, started flowing into Syria, and most of them chose to live in Damascus.

The stories told by refugees who escaped the “Iraqi hell” contributed to molding the feelings of the Syrians. By way of those stories and experiences, many Iraqis brought their political and sectarian divisions to Syria. The economic pressure represented by the presence of these huge numbers of Iraqis in Syria — at a time when the Syrian state was increasingly marred by corruption and loosening social safety nets through the increasing adoption of economic liberalism — contributed to fueling the economic and social problems that paved the way for Syrian protests at a later stage.

The support that Syrian opposition groups received from regional Sunni powers is also related to these powers’ desire to counter Iranian influence in Iraq. They wanted to win Syria in order to compensate for their loss in Iraq.

The idea of keeping Syria “out of Iraq” currently looks like an illusion that doesn’t differ much from the previous one of distancing Syria from Iraq. The two countries offer a new model for a region in which the state is decomposing, and where inter-state solidarities are flourishing. The destinies of the two countries are connected today more than ever.

Harith Hasan is an Iraqi scholar and writer. He has a PhD in political science and his main research interests are state-society relations and identity politics in Iraq and the Arab Mashriq. On Twitter: @harith_hasan

http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/09/syria-iraq-geography-mythology-conflict.html

.

The first king in Iraq after its separation from the Ottoman Empire was also previously the king of Syria. However, as Iraq and Syria were under the control of two different powers (Britain in the case of Iraq, and France in the case of Syria), they were not governed by King Faisal I during the same period.

The Baath party failed to unify Syria and Iraq, despite the fact that the party’s ideology was based on the idea of Arab unity and its branches ruled the two countries simultaneously. This failure was a result of the unique relationship between the two, one which is characterized by strong similarities and discord at the same time.

Iraqi politician Ahmad Chalabi’s recent — albeit unrealistic — call to establish a confederation bringing together the two countries signals a continued lack of faith in the feasibility of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which set the borders of the two countries.

While that call lacks seriousness, the biggest paradox is that the al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS, also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) has become the first political-military organization to deal practically with the two countries as a single political unit.

An important aspect of the religious and sectarian divide in the region is based on the historic conflict in the seventh century between the army of Ali bin Abi Talib, the fourth Islamic caliph based in Kufa, Iraq, and the army of Muawiyah Ben Abi Sufyan, the Umayyad dynasty founder who settled in Damascus.

A great deal of the sectarian tension currently plaguing the two countries results from historical conflicts, and from telling the story of these conflicts in a way that serves the different parties in their current confrontations.

However, the issue goes beyond ideology, reaching actions on the ground. At a time when many people are talking about the need to stop the Syrian civil war from extending to Iraq, it is worth mentioning that the relationship between the two countries and their respective turmoil existed even before the outbreak of the protests in Syria.

The political and social transformation in Iraq that followed 2003 had a significant effect on Syria. President Bashar al-Assad's regime tried to be in harmony with the will of the majority of Syrians in opposition to the war and its consequences, but probably for different reasons. Syria allowed the flow of foreign fighters to fight the US forces in Iraq. The insurgency, however, led to results that would affect Syria at a later stage.

Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees, including opponents of the regime, started flowing into Syria, and most of them chose to live in Damascus.

The stories told by refugees who escaped the “Iraqi hell” contributed to molding the feelings of the Syrians. By way of those stories and experiences, many Iraqis brought their political and sectarian divisions to Syria. The economic pressure represented by the presence of these huge numbers of Iraqis in Syria — at a time when the Syrian state was increasingly marred by corruption and loosening social safety nets through the increasing adoption of economic liberalism — contributed to fueling the economic and social problems that paved the way for Syrian protests at a later stage.

The support that Syrian opposition groups received from regional Sunni powers is also related to these powers’ desire to counter Iranian influence in Iraq. They wanted to win Syria in order to compensate for their loss in Iraq.

The idea of keeping Syria “out of Iraq” currently looks like an illusion that doesn’t differ much from the previous one of distancing Syria from Iraq. The two countries offer a new model for a region in which the state is decomposing, and where inter-state solidarities are flourishing. The destinies of the two countries are connected today more than ever.

Harith Hasan is an Iraqi scholar and writer. He has a PhD in political science and his main research interests are state-society relations and identity politics in Iraq and the Arab Mashriq. On Twitter: @harith_hasan

http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/09/syria-iraq-geography-mythology-conflict.html

History of Syria

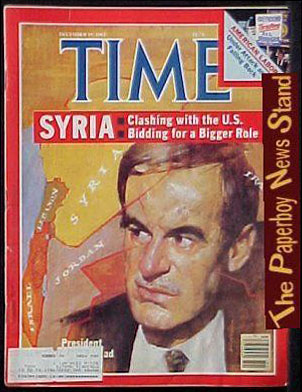

| HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Present-day Syria is only a small portion of the ancient geographical Syrian landmass, a region situated at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea from which Western powers created the contemporary states of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel in the post-Ottoman era of the early twentieth century. Greater Syria, as historians and political scientists often refer to this area, is a region connecting three continents, simultaneously cursed and blessed as a crossroads for commerce and a battleground for the political destinies of dynasties and empires. Exploited politically, Greater Syria also has benefited immeasurably from the cultural diversity of the people who came to claim parts or all of it, and who remained to contribute to the remarkable spiritual and intellectual flowering that characterized Greater Syria’s cultures in the ancient and medieval periods. Throughout history, Greater Syria has been the focal point of a continual dialectic, both intellectual and bellicose, between the Middle East and the West. Today, Syria remains an active participant in the trials and tribulations of a troubled and volatile region. Early History Since before 2000 BC, Syria has been an integral part of, or the seat of government for, powerful empires. The struggle among various indigenous groups as well as invading foreigners resulted in cultural enrichment and significant contributions to civilization, despite political upheaval or turmoil. The ancient city of Ebla existed at the center of an expansive empire around 2400 B.C. The chief site, unearthed in the vicinity of Aleppo in the 1970s, contained tablets providing evidence of a sophisticated and powerful indigenous Syrian empire that was involved with, and probably controlled, a vast commercial network linking Anatolia (today part of Turkey), Mesopotamia (an ancient region of southwestern Asia in present-day Iraq), Egypt, and the Aegean and Syrian coasts. The language of Ebla is believed to be the oldest Semitic language, and the extensive writings of the Ebla culture are proof of a brilliant culture that rivals those of the Mesopotamians and ancient Egyptians. After the King of Akkad (Mesopotamia) destroyed Ebla, Amorites ruled the region until their power was eclipsed in 1600 B.C. by the Egyptians. The following centuries saw Syria ruled by a succession of Canaanites, Phoenicians, Hebrews, Aramaeans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Seleucids, Romans, Nabataeans, Byzantines, Muslim Arabs, European Christian Crusaders, Ottoman Turks, Western Allied forces, and the French. Although Syria has absorbed the legacies of these many and varied cultures, the very existence of this string of foreign dominating powers exemplifies the political, economic, and religious importance of Syria’s strategic location. Highlights of early Syrian history include the impact made by such dominant powers as the Phoenicians, Aramaeans, and Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Empires. During the second millennium B.C., the seafaring Phoenicians established a trade network among independent city-states and developed the alphabet. The Aramaeans, overland merchants who had settled in Greater Syria at the end of the thirteenth century B.C., opened trade to southwestern Asia, and their capital at Damascus became a city of immense wealth and influence. Aramaic ultimately displaced Hebrew as the vernacular in Greater Syria and became the language of commerce throughout the Middle East. Beginning in 333 B.C., with the conquest of the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great and his successors brought Western ideas and institutions to Syria. Following Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., control of Greater Syria passed to the Seleucids, who ruled the Kingdom of Syria from their capital at Damascus for three centuries. In the first centuries A.D., Roman rule saw the advent of Christianity in Syria. Paul, considered to be the founder of Christianity as a distinct religion, was converted on the road to Damascus and established the first organized Christian Church at Antioch during the first century. The Coming of Islam Syria remained at the center of the new Christian religion until the seventh century, when the area succumbed to Muslim Arab rule. Prior to the Arab invasion, Byzantine oppression had catalyzed a Syrian intellectual and religious revolt, creating a Syrian national consciousness. The Muslim Arab conquest in A.D. 635 was perceived as a liberating force from the persecution of Byzantine rule, to which Syria had been subjected since A.D. 324. But with Damascus as the seat of the Islamic Umayyad Empire, which extended as far as Spain and India between 661 and 750, most Syrians became Muslim, and Arabic replaced Aramaic. Syrian prestige and power declined after 750 when the Abbasids conquered the Umayyads and established a caliphate in Baghdad. Syria then became a mere province within an empire. Muslim control of Christian holy places was elemental in provoking the first major Western colonial venture in the Middle East, when European Crusaders established the principalities of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem between 1097 and 1144. The ensuing jihad against the foreign occupation was a unifying force for Arabs in Greater Syria until the area became a province of the Ottoman Empire in 1516. Syria’s economy did not flourish under Ottoman rule, which lasted for 400 years. Yet, Syria continued to attract European traders and with them Western missionaries, teachers, scientists, and tourists whose governments began to agitate for certain rights in the region, including the right to protect Christians. A Brief Period of Independence The period between the outbreak of World War I in 1914 and the granting of France’s mandate over Syria by the League of Nations in 1922 was marked by a complicated sequence of events during which Syrians achieved a brief period of independence (1919– 20). However, three forces were at work against Arab nationalism: Britain’s interest in keeping eastern Mesopotamia under its control in order to counter Russian influence and to protect British oil interests; the Jewish interest in Palestine; and France’s determination to remain a power in the Middle East. Ultimately, Syria and Lebanon were placed under French influence, and Transjordan and Iraq, under British mandate. The termination of Syria’s brief experience with independence left a lasting bitterness against the West and a deep-seated determination to reunite Arabs in one state. This quest was the primary basis for modern Arab nationalism. The French Mandate The period of French Mandate brought nearly every feature of Syrian life under French control. This oppressive atmosphere mobilized educated wealthy Muslims against the French. Among their grievances were the suppression of newspapers, political activity, and civil rights; the division of Greater Syria into multiple political units; and French reluctance to frame a constitution for Syria that would provide for eventual sovereignty, which the League of Nations had mandated. Only in the wake of a widespread revolt instigated by the Druze minority in 1925 did the French military government begin to move toward Syrian autonomy. Despite French opposition, the Soviet Union (today Russia) and the United States granted Syria and Lebanon recognition as sovereign states in 1944, with British recognition following a year later. These Allied nations pressured France to leave Syria, but it was not until a United Nations resolution in February 1946 ordering France to evacuate that Syrians finally attained sovereignty. By April 15, 1946, all French troops had left Syrian soil. Independence Syria endured decades of strife and turmoil as competing factions fought over control of the country’s government following independence in 1946. This era was one of coups, countercoups, and intermittent civilian rule during which the army maintained a watchful presence in the background. From February 1958 to September 1961, Syria was joined with Egypt in the United Arab Republic (UAR). But growing Syrian dissatisfaction with Egyptian domination resulted in another military coup in Damascus, and Syria seceded from the UAR. Another period of instability ensued, with frequent changes of government. The Arab Socialist Resurrection (Baath) Party (hereafter, Baath Party), with a secular, socialist, Arab nationalist orientation, took decisive control in a March 1963 coup, often referred to as the Baath Revolution. The Baath Party had been active throughout the Middle East since the late 1940s, and a Baath coup had taken place in Iraq one month prior to the Baath take-over in Syria.

Assad, approved as president by popular referendum in March 1971, quickly moved to establish an authoritarian regime with power concentrated in his own hands. His thirty- year presidency was characterized by a cult of personality, developed in order to maintain control over a potentially restive population and to provide cohesion and stability to government. The dominance of the Baath Party; the socialist structure of the government and economy; the military underpinning of the regime; the primacy of members of the Alawi sect, to which Asad belonged, in influential military and security positions; and the state of emergency imposed as a result of ongoing conflict with Israel further ensured the regime’s stability. Nevertheless, this approach to government came at a cost. Dissent was harshly eliminated, the most extreme example being the brutal suppression in February 1982 of the Muslim Brotherhood, which objected to the state’s secularism and the influence of the “heretical” Alawis. Moreover, the country’s economy suffered, and progress was hindered by an overstaffed and inefficient public sector run overwhelmingly according to Baath Party dictates.

Hafiz al Assad died in 2000 and was promptly succeeded by his son, Bashar al Assad, after the constitution was amended to reduce the mandatory minimum age of the president from 40 to 34. Bashar was then nominated by the Baath Party and elected president in a popular referendum in which he ran unopposed. From the start, the younger Assad appeared to make economic and political reform a focus and a priority of his presidency. He has faced resistance from the old guard, however. After a brief period of relaxation and openness known as the Damascus Spring (July 2000–February 2001), dissent is once again not tolerated in Syria, and it appears that any reforms will be slow in coming. Nevertheless, Assad reportedly is slowly dismantling the old regime by enforcing mandatory retirement and replacing certain high-level administrators with appointments from outside the Baath Party. 2011 Syrian Uprising Syria was under an Emergency Law since 1962, effectively suspending most constitutional protections for citizens. Its President Hafez al-Assad led Syria for nearly 30 years, banning any opposing political party and any opposition candidate in any election. The Syrian government justified the state of emergency to the fact that Syria was in a state of war with Israel. According to BBC News, the government and ruling Ba'ath Party own and control much of the media. Criticism of the president and his family is banned and the domestic and foreign press are censored. The state exercises strict internet censorship and blocks many global websites with local appeal, including Facebook and YouTube, as well as opposition sites. The popular uprising, taking place in various cities in Syria, began on 26 January 2011. Like other pro-democracy rebellions which have erupted across the Middle East, the protests have taken the form of various types, including marches and hunger strikes. In reacting to the largest uprising to take place in the country for decades, Syrian security forces have killed hundreds of protesters and injured many more. Source: Library of Congress and others |

|||||

| More about Syria: Cities: Country: Syria key statistical data. Continent: External Links: Syrian History A Syrian website documenting the recent history of Syria, from 1900 to 2000, by Sami Moubayed. Wikipedia: History of Syria Wikipedia article about the History of Syria. |

.

| http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/History/Syria-history.htm |

Comments

Post a Comment